|

Today we were in resus for a run through of how we would assess, investigate and treat an adult patient presenting in SVT. We looked at the decision making that is required to safely and efficiently manage their care.

The simulated case:

A 66 year old male, who noticed a sudden onset of palpitations at home this morning, approximately 3 hours ago. He’s feeling subjectively unwell, though denies any pain. He’s never felt like this before. He has a background of hypertension - controlled with an ACE inhibitor - and smokes around 10 cigarettes per day. He arrived by ambulance, and as a result of his fast heart rate was directed straight to resus, where the sim team took over. What happened? Steven was only complaining of a pounding sensation in his chest and feeling “unwell”, though couldn’t elaborate much further. His 12 lead ECG showed narrow complex regular tachycardia with absent P waves, suggestive of an SVT.

What did we think?

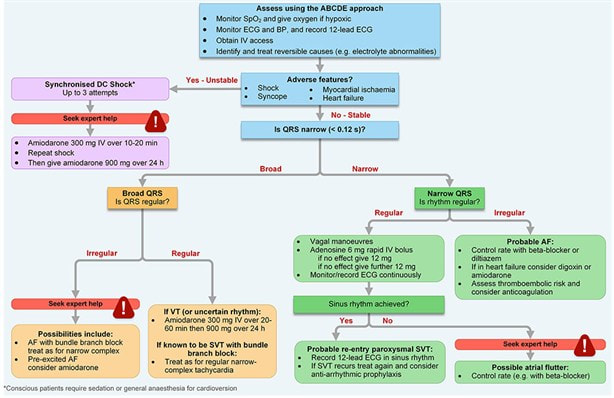

In debrief we discussed: Treatment strategies: “Adverse features” that are essential to assess for are: Myocardial Ischaemia Shock Syncope Heart Failure These can indicate the need for DC cardioversion. An effective ABCDE assessment and primary survey of the acutely ill adult, coupled with effective history taking is therefore key to managing this case. As with all situations, the ground can shift and regular reassessment is essential. Non-technical skills: We discussed decision heuristics and non-technical skills in the context of a stressful and rapidly changing scenario. The effective use of mini-summaries really helped the team share the mental model and understand the direction the case was progressing in. Situations where decision making needs to be challenged were reviewed, and we talked about speaking up using the PACE format: Probe - “are you sure about…” Alert - “don’t you think this will cause…” Challenge - “I’m afraid this is going to harm the patient…” Emergency action - “STOP what you are doing! I will get help…” The guidelines: ALS Tachydysrhythmia Guidance: (See original quality version here) REVERT team discussing the Modified Valsalva Manoeuvre: (original link here)

To do: RCEM learning on SVT here [ ] If you took part in the sim, you can use this blog as a starter to reflect on your own experience of it [ ] Blog by: Joey Giles, Senior Advanced Clinical Practitioner --------------- For clinical decisions please refer directly to the guidance. This blog may not be updated. All images copyright- and attribution-free in the public domain or taken by the author.

4 Comments

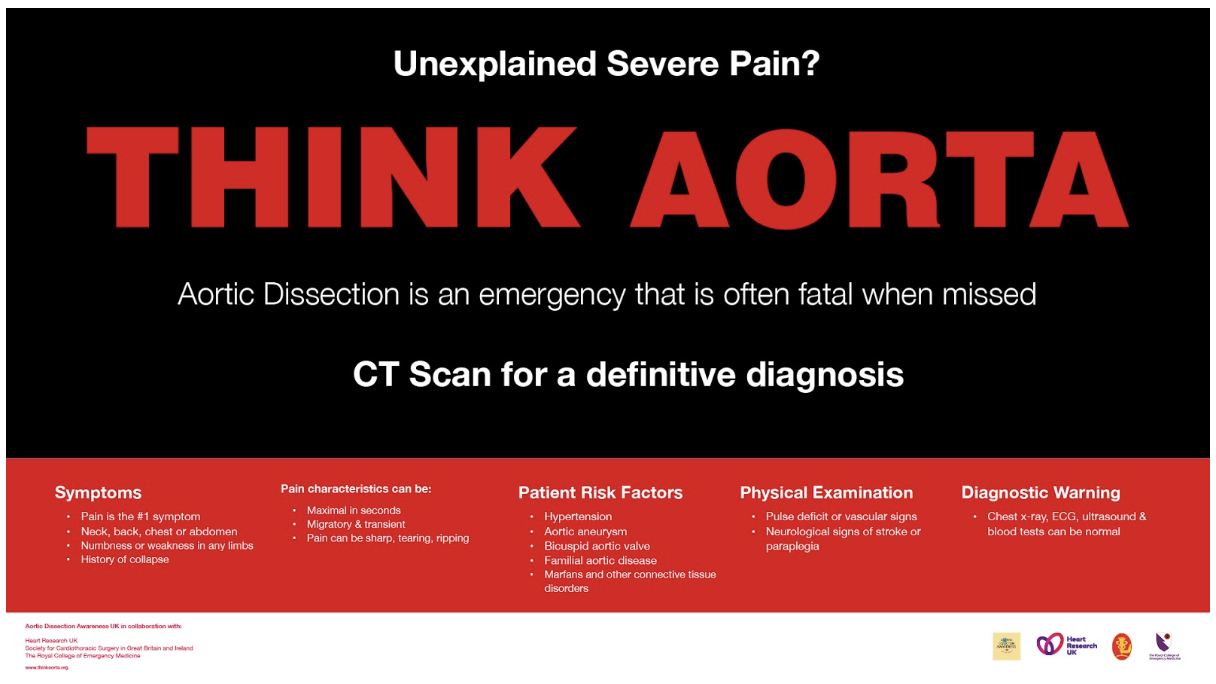

We were in ambulatory today thinking about the sort of patient that can slip under the radar. This was a patient with chest pain for whom aortic dissection was also a diagnostic possibility. The simulated case: A 66 year old man with hypertension, who has had sharp chest-through-to-back pain that started while out walking his dog. Think about cases where you have considered aortic dissection or seen it considered by other people - what are the aspects that raise it as a possibility? What happened?

The patient had their blood taken in START, and was brought through into ambulatory for observations and an ECG. After a history and exam, aortic syndrome was considered more likely and they were transferred to majors while awaiting urgent CT angiogram. What did we think? In debrief we discussed: Threshold for considering the aorta: Aortic dissection can present in a variety of ways, and is often not the top diagnosis for the given presentation, so there needs to be a low threshold for considering it and looking for it. Although relatively uncommon, the high number of patients coming through ED means there could be around 1 per month in Derriford ED. Some resources refer to “chest pain plus one” where one looks for an additional feature alongside the chest pain that makes it atypical - e.g. back pain, abdominal pain, neurological changes. Mostly we are looking for:

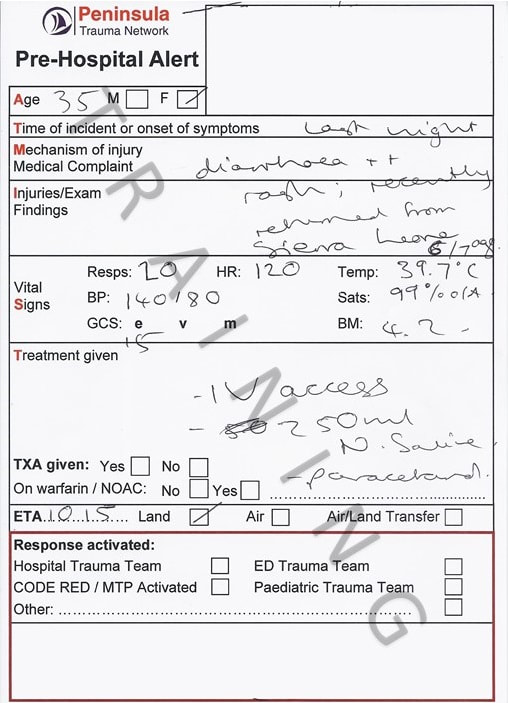

There may be a pulse deficit or different BP in each arm, but these signs are not common and their absence does not exclude the diagnosis. In debrief we reviewed a chest x-ray with widened mediastinum, but again this is uncommon and a normal chest x-ray does not exclude aortic dissection. Logistics: The patient needed to move from ambulatory majors, for which the nurse in charge desk can be phoned to arrange. Patients would also need to move before they can have oxygen. They required an urgent CT angiogram, which also means a green cannula is needed. We thought about whether this patient might need an escort for the CT or not. Blood pressure management: The aortic dissection guideline on EDIS gives clear instructions regarding the management of blood pressure using labetalol. The target is a pulse of around 60 bpm and systolic BP under 110-120mmHg. If there is a discrepancy between arms the aim is to bring the higher result down, although one would need to be mindful not to drop the lower BP below the level required to perfuse. Closed loop communication: We talked about the use of closed-loop communication in this case to ensure tasks are being completed. The guidelines: The guideline is on EDIS under “adult medicine” and then “cardiology”. To do: Listen to “the aorta will #@&$! you up” (20 mins) online lecture here [ ] RCEM e-learning here [ ] If you took part in the sim, you can use this blog as a starter to reflect on your own experience of it [ ] James Keitley - ED Sim Fellow --------------- For clinical decisions please refer directly to the guidance. This blog may not be updated. All images copyright- and attribution-free in the public domain or taken by the author. SimFridays sessions never seem to be on a Friday lately... so will be called "Sim ED" now instead! We did something a bit different and a bit scary in this one, and practised management of a patient with viral haemorrhagic fever (VHF). This tested our knowledge, team-working, and also the laboratory processes. The simulated case: Tanya is a woman in her thirties presenting with bloody diarrhoea, fever and a petechial rash. She returned 5 days ago from volunteering in Sierra Leone. What are the possible causes of this? Which of these are most common? Which are most serious? How would you approach a patient like this to cover the serious ones without overlooking common causes?

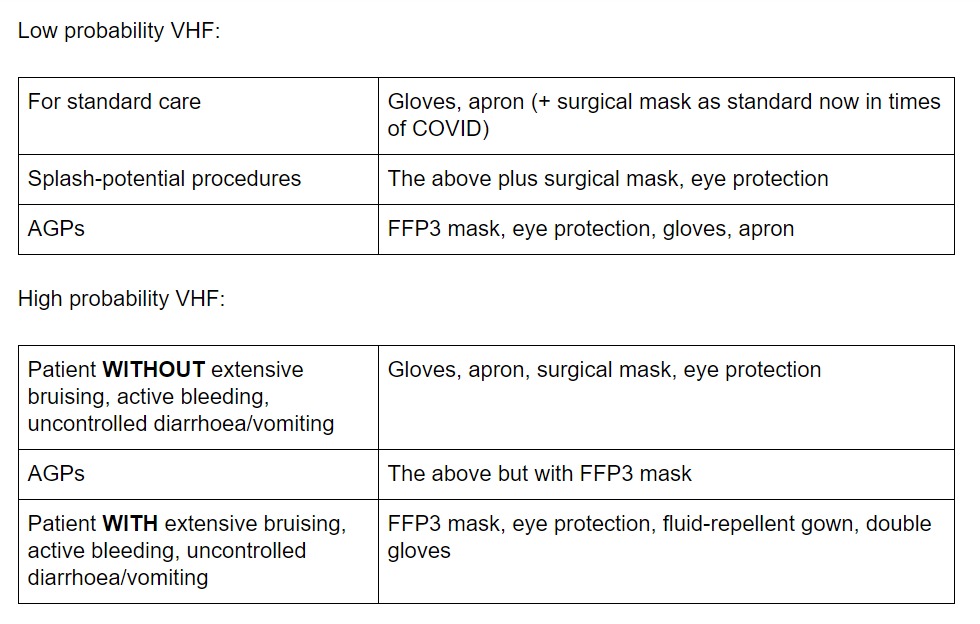

What did we think? In debrief we discussed: Horses vs zebras: From the outset of this simulation there was consideration of which diseases are endemic in the country the patient had visited, and VHF was considered likely. As a result one clinician reviewed alone in PPE and there were long discussions about tests, who to contact etc. It was pointed out that still common things are common and tasks like taking observations, giving fluids and antibiotics should not be delayed. Diagnoses like infectious gastroenteritis, sepsis, and even malaria are comparatively common so we need to both be wary of the serious but rare diagnosis whilst also cracking on with management of the more common options. Don’t forget the basics to avoid missing the horses! A really good A-E with attention to all vital signs and a brief history will help you act on the important horses question: IS THIS SEPSIS?... And treat it expeditiously. Explaining to the patient: Clearly coming to hospital in these circumstances would be very scary. I thought the patient explanations here were great and managed to explain the seriousness of the situation, gave clear instructions (“please do not leave the room”) whilst also being quite reassuring that the team had a good plan of what to do. Logistics of isolation and PPE: See the guidelines section below for what the SOP tells us about isolation for VHF. In this scenario the patient was isolated in a side room of majors. We discussed that a patient isolated like this must either have an en suite bathroom or at least a dedicated commode, and that this is very difficult to provide at present. We will be looking to source more. The patient’s blood sample labels were printed elsewhere by the runners and passed into the room to be applied to the samples. They were bagged once within the isolation room and dropped into a second bag held outside the room, before being put into a haze container and transported to the lab on foot. Clearly tasks like this require a good enough level of staffing to have people available nearby. The labs can send staff to collect the samples… don’t be afraid to ask for this when speaking to them.

Testing: The guidelines section below highlights specific requirements. In this scenario there were debate as to whether to delay taking blood until after the discussion with microbiology to ensure the correct samples were collected. Each time a sample is taken from a highly infectious patient there will be risk involved, so perhaps it is sensible if there is no immediate need, to confirm the tests first with the expert. We talked about how it has become automatic to process a venous blood gas for all patients. Because of splash risk it isn’t recommended in possible VHF cases, so perhaps one to think twice about how the results might change our management. Speaking to other teams: In the case of VHF there are many external people that need informing (see guidelines below). We talked about how long these discussions can take, and the importance of having concurrent tasks occurring that utilise different members of the team. Speaking up: We talked about team dynamics and the importance of speaking up and reminding the rest of the team of key actions. In this sort of rare presentation, it will be common to feel out of one’s depth and unsure, using your team to check any missed actions or specifically to read out the SOP is really helpful. As this blog has mentioned previously, closed loop communication (including use of first names) to confirm tasks, and graded assertiveness (see previous post on this) to remind others in the team, are both important. The guidelines: Probably the easiest place to find guidelines quickly for this patient is to go to the StaffNet homepage and use the search bar to find “viral fever” or “VHF”. The top option is an infection control page that talks about many diseases on different tabs, including VHF and Ebola. Alternatively there is a version inside the G drive under “Trust Documents”. I will highlight key parts here as a quick read. Please go to the source for the full info: Overview of VHF (info source Trust guidelines):

Triage assessment: If we know ahead that such a patient is coming, they should remain in the car park until cubicle 11 is ready for them to be transferred to directly. There is a VHF risk assessment flowchart on a single side of paper which you can easily follow to assess the likelihood of VHF. It also has brief but clear outcomes depending on the likelihood, and an overview of PPE required. This for me is the key part of the guidelines you must print for patients where it is being considered. There are negative-pressure isolation rooms in other departments, so ideally if VHF is considered likely from our flowchart the patient should be transferred to one of these via the bed manager or duty senior nurse, and then managed by the medical take team. Who to tell? Microbiology first. If thought to be likely VHF, switchboard can be asked to undertake the “critical internal incident call-out cascade” which will inform the necessary internal staff and open a major incident. The on-call director will then inform Public Health England and the other external agencies. Isolation and PPE: Side room with either en-suite bathroom or a dedicated commode. Ideally negative-pressure. The guidelines state exactly how to deal with laundry, spillages, waste etc. If the VHF screen comes back as positive the patient should be transferred to a HLIU (Royal Free London) and the local health protection team will be involved.

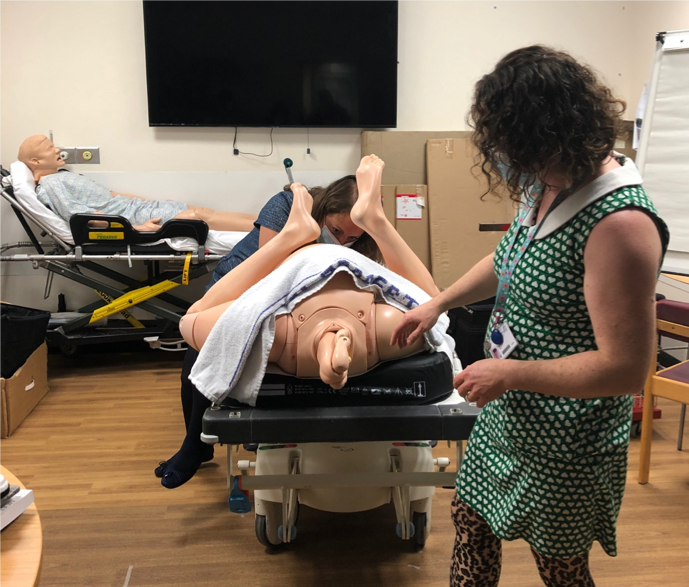

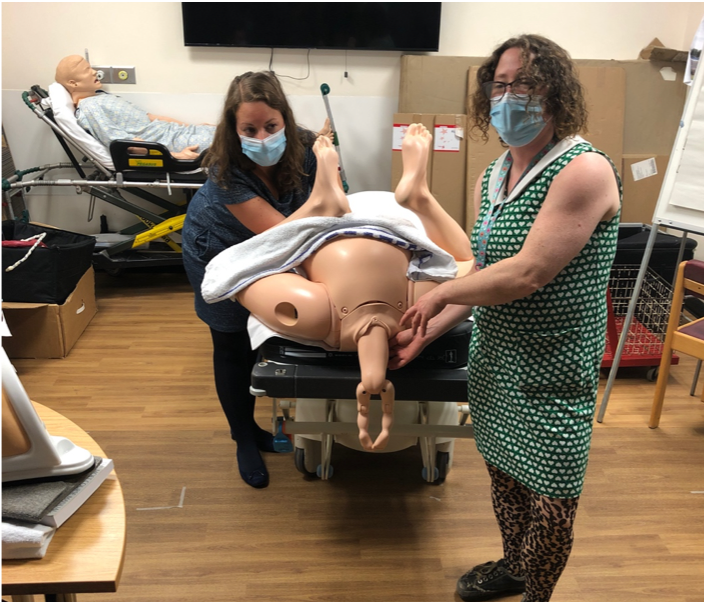

Testing: Urgent malaria testing (EDTA tube), FBC, U+Es, LFTs, clotting, CRP, glucose, blood cultures. Must call the combined labs ahead to inform them of the potential case. If high risk, they will send a haze container for the samples to be put inside. Must ask for a named contact in the lab to hand the sample to and provide a number to contact us back on. Must not use the pod system. The consultant microbiologist will organise the VHF screen from their side. The test is done on 1 x EDTA and 1 x clotted serum tubes. So, overall likely to need 3 x purple EDTA tubes, 2 x yellow serum tubes, 1 x blue and blood cultures. It is recommended generally not to use point-of-care blood gas testing due to splash-risk (Shorten and Wilson-Davies 2017). Management of contacts: If a patient has a “high probability” of VHF, a register must be kept of all staff entering the patient’s room (there is one ready to print in the guideline appendix). There are tables for how to manage contacts on pages 20 and 21 of the guidelines. Generally it involves self-monitoring temperature and reporting if symptoms develop. Interestingly, even for the highest risk contact (e.g. mucosal splash, needlestick, sexual contact) there are no restrictions on work or movements if asymptomatic, but they must monitor temperature and report to the monitoring officer daily. To do: Consider the next time you know ‘red PPE’ will be required for a case whether the donning/doffing guides in the PPE cupboard will be helpful to have nearby [ ] Have a look at the single-page risk assessment for VHF on StaffNet [ ] If you took part in the sim, you can use this blog as a starter to reflect on your own experience of it [ ] See you next time, James Keitley - ED Sim Fellow --------------- For clinical decisions please refer directly to the guidance. This blog may not be updated. All images copyright- and attribution-free in the public domain or taken by the author. Today we tried something different in a sim session… O&G Consultant Tim came down to ED with two of his registrars (Steph and Amy) and we rotated through two obstetric emergencies in ED stations… socially distanced of course but let me tell you, there is NOTHING socially distanced about the raw practice of delivering a baby! Amy and Steph talked us through a normal delivery: Should present face down, deliver the head, then allow “Restitution” – where the baby rotates to fit the torso through the birth canal. On the next contraction – the anterior(upper) shoulder should deliver then posterior shoulder. Now breathe yourself…. And if the baby is breathing – there is no rush to cut cord, you can give the baby a quick dry and a rub and put it skin to skin with mum… job done! Then, we talked through and delivered a baby with the absolutely EMERGENCY finding of Shoulder dystocia… code very, very scary… This is where the baby’s shoulder is stuck behind mum’s symphysis pubis… Risk factors – obesity in mum, gestational DM – big baby Head may deliver slowly, ‘turtle necking’, undelivered chin. May not restitute fully No progression on second contraction This is completely Time critical– as a team we have only a few minutes to prevent a hypoxic brain injury/death… here is the SOP:

Be aware that you may cause fractures to humerus/clavicle, this is totally OK if you can baby out alive…. Super scary… let’s hope those 2222 bleep holders can run fast and have mini, super strong hands!! Give this a watch: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1HeXmlf_sp4 Our obstetric registrar friends also talked us through how to deliver a baby presenting as a Breech delivery… First thing: This May be very quick in multiparous women – be prepared to catch! You will notice that buttocks are presenting. The baby is facing posteriorly (down)… Bring mum to the end of bed. This is a hands off situation. Minimal handling of the baby will avoid stimulation that will promote breathing (while head still inside)/increased metabolism/oxygen consumption. If handling is required - only to the bony pelvis/hips of the baby. Allow the buttocks to deliver – allow baby to hang down The hips will probably be flexed and knees extended, you can use your finger to ‘flick’ them out: Allow delivery until the shoulder blades are seen The arms can be delivered by gentle rotation of baby at hips Or Sweeping the arms over the baby’s face with a finger The neck/head needs to flex to allow narrowest cross section to pass through the birth canal.

Again, have a watch of this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EWjKswZ3Mm8 And that if that didn’t get our hearts racing fast enough, we also spent an hour chatting to Tim about resuscitating the pregnant patient in a peri-arrest or cardiac arrest situation, medications during pregnancy, post partum haemorrhage management and pre-eclampsia treatments… The harsh fact is maternal mortality is not falling, despite improvements in care because patients are becoming increasingly complex… While we work at Derriford ED, we need to know a few things about obstetric emergencies: 30993 – Labour ward emergency phone – useful if putting out a 2222 – tell them what the problem is – so they know what to bring eg – shoulder dystocia (run very, very fast and get here yesterday) vs PPH (come quickly). As a refresher, we reminded ourselves of the physiological changes that occur in pregnancy, affecting every letter from A-E… check out the PROMPT course for more on that or read your ALS special circumstances chapter… Here area few pearls from Tim’s talk:

Resuscitation in pregnancy…also a scary subject… Same principles as any other resuscitation but do not forget:

Now the thorny subject of PE/VTE disease in pregnancy…. A negative D-dimer is probably useful in low pre-test probability patients but what about imaging?? V/Q vs CTPA

We had a great chat about managing Post-Partum Haemorrhage (PPH) Primary PPH occurs up to 48 hours of delivery vs Secondary PPH which occurs after 48hours (secondary is much more likely to be infective) Resuscitate – as for haemorrhagic shock – think blood products, rotem, calcium etc. Give antibiotics if suspected infection (so nearly all secondary PPH)… We all love the 4Hs and 4Ts of cardiac arrest causes… but in obstetrics, let’s not forget the 4 T’s of PPH: Tone– Most common, the uterus is exhausted after its big night out (push,push, push) and needs a hormone to increase uterine contraction – ergometrine/syntometrine/misoprostil. (caution if hypertensive). We keep ergometrine in our ED resus drug cupboard: Tim also reminded us about using Bimanual compression in these ladies: put a fist into the vagina while also applying fundal pressure – it should be painful/tiring if effective (may need to change operator). Here is Tim showing us the desired effect on the tired atonic uterus…. On those 4Ts also think:

Trauma–a simple perineal tear possibly… – if arterial, can bleed quickly – fresh red blood is likely to be perineal: is it possible to put a quick suture in place and apply pressure? Tissue– Retained products? Check the placenta after eth delivery of the baby and placenta, is there a chunk missing or ragged membranes, suggesting some may remain in mum’s uterus? And finally: Thrombin– Are they forming clots? – A DIC picture represents fairly advanced bleeding… we need ROTEM to help us… along with the expertise of the obstetric team… resuscitate with blood products asap. Briefly, we considered another obstetric emergency presentation we may see in ED: Eclampsia Usually we will see a patient presenting with a headache and Hypertension and/ or proteinuria (can occur without either but very rare). This is pre-eclampsia… It is of unknown cause but may progress to seizures – give MgSO4 - 4g in 20mls saline over 20 mins (double the typical ED dose for asthma etc) Use labetalol for BP control…. And that was our multiprofessional interactive, hands on, socially distanced morning…. More soon, watch this space! With huge thanks to the obstetric team of Tim, Amy and Steph, to James Keitley for his unwavering enthusiasm for education and awesome administrative support today and to Neil Spencer for lending me his notes to Annetticise… |

Categories

All

The Derrifoam BlogWelcome to the Derrifoam blog - interesting pictures, numbers, pitfalls and learning points from the last few weeks. Qualityish CPD made quick and easy..... Archives

October 2022

|