|

February is endocrine-themed, and I’ve tried to pick out cases that I have had difficulties with or reflected upon. We see patients with hyponatraemia all the time, but not so often are they severely deficient or symptomatic. The simulated case: A woman in her 60s presenting after a minor fall in her shower, reported to be acting strangely by her family. She has come through START and initial investigations have shown a sodium level of 113. She has been moved to resus. What happened? The ACP looked at her previous blood tests and her recent GP consultation record, which showed her sodium had been normal 4 months ago and that she had consulted about a long-term cough but had been lost to follow-up. After examination there was no suspicion of traumatic injuries from the fall. She had formal bloods taken, an ECG (sinus tachycardia), and a second cannula. Additional blood tests like bone profile, magnesium, osmolality calculation were added on, and a urine sample was planned to test osmolality and urinary electrolytes. A chest x-ray showed a large unilateral pleural effusion. As per the guideline a plan was made to give 150mL of 2.7% sodium chloride IV. What did we think? In debrief we discussed: Immediate management considerations: Severe hyponatraemia puts the patient at risk of seizures, coma and arrest. In this simulation they had the symptom of confusion. The guideline (see the ‘to do’ section for its location) recommends 150mL of 2.7% hypertonic saline over 20 minutes followed by a sodium check, aiming for 5mmol/L increase over 1 hour. Overall we’re aiming for no more than 10mmol/L increase in the first 24 hours to reduce risks of demyelination. It was difficult to find the hypertonic saline at the time of the sim - this will be looked into. Although we may not see the results in ED, it’s helpful to have paired serum and urine osmolalities, urinary electrolytes and TFTs as well as the standard bloods. After initial management the subsequent steps will rely on this information. A random cortisol is less helpful than a 9am one, but may be helpful if Addisonian crisis is suspected as the cause. Note if starting fluid restriction this should be at about 500mL less than the patient’s usual intake, but otherwise interestingly the restriction amount can actually be estimated using the urinary electrolyte results - have a look at the guideline. Causes of hyponatraemia: It’s worth considering potential causes of pseudohyponatraemia: having high triglycerides, high serum protein levels or taking blood during an infusion can falsely alter the reported sodium level. Otherwise, for hyponatraemia, as per the guideline the causes can be organised by whether they cause a hypovolaemic, euvolaemic or hypervolaemic state. So it's really critical to consider the patient's fluid status. You can then consider some of the causes:

Fluid overload state: all the “failures” - cardiac failure, renal failure/nephrotic syndrome. Euvolaemia: low intake of salt, SIADH, hypothyroidism, medications, surgery. Dehydrated: vomiting, diarrhoea, Addison’s, nephritis, salt wasting syndrome. In terms of SIADH which caused this patient’s hyponatraemia, there are further causes to consider. The patient has potentially had a head injury which can cause low sodium, but they have also had a cough and abnormal chest x-ray. This could represent pneumonia which can cause hyponatraemia. However their history of several months cough and weight-loss on a background of COPD and smoking, with pleural effusion on x-ray, may represent a small cell lung cancer producing ectopic ADH. The part of the guideline for asymptomatic or chronic hyponatraemia takes you through the different investigation depending on fluid status and urine osmolality. Mechanism of hyponatraemia: I’ve always found it tricky to think through why in SIADH patients can be euvolaemic with hyponatraemia and why this isn’t corrected. I found this video resource great for working through it. In essence, the excess ADH increases aquaporin expression in the nephron, more water is reabsorbed through these and blood volume increases. But then, in response to the increased fluid volume in the body, the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis is downregulated, there is reduced aldosterone action, overall causing loss of sodium WITH water. Eventually there is some adaptation and the kidneys become less sensitive to ADH. Overall the net effect is euvolaemia but with loss of sodium. Decision whether to request a CT head: It was decided that the patient would benefit from a CT head scan, but this was judged to be currently lower priority than the other management steps. In this case it would have been normal. To do: Have a watch of this video explaining SIADH [ ] Ensure you know where to find hypertonic saline in ED [ ] Refresh yourself on the acute hyponatraemia guideline, go into the G: drive, clinical guidelines, then click to search for hyponatraemia [ ] If you took part in the sim or watched on the livestream, you can use this blog as a starter to reflect on your own experience of it [ ] Thank you to Laura for being our simulated patient today. Blog by: James Keitley - ED sim fellow - on behalf of the ED sim team. --------------- For clinical decisions please refer directly to primary sources. This blog may not be updated. All images copyright- and attribution-free in the public domain or taken by the author.

0 Comments

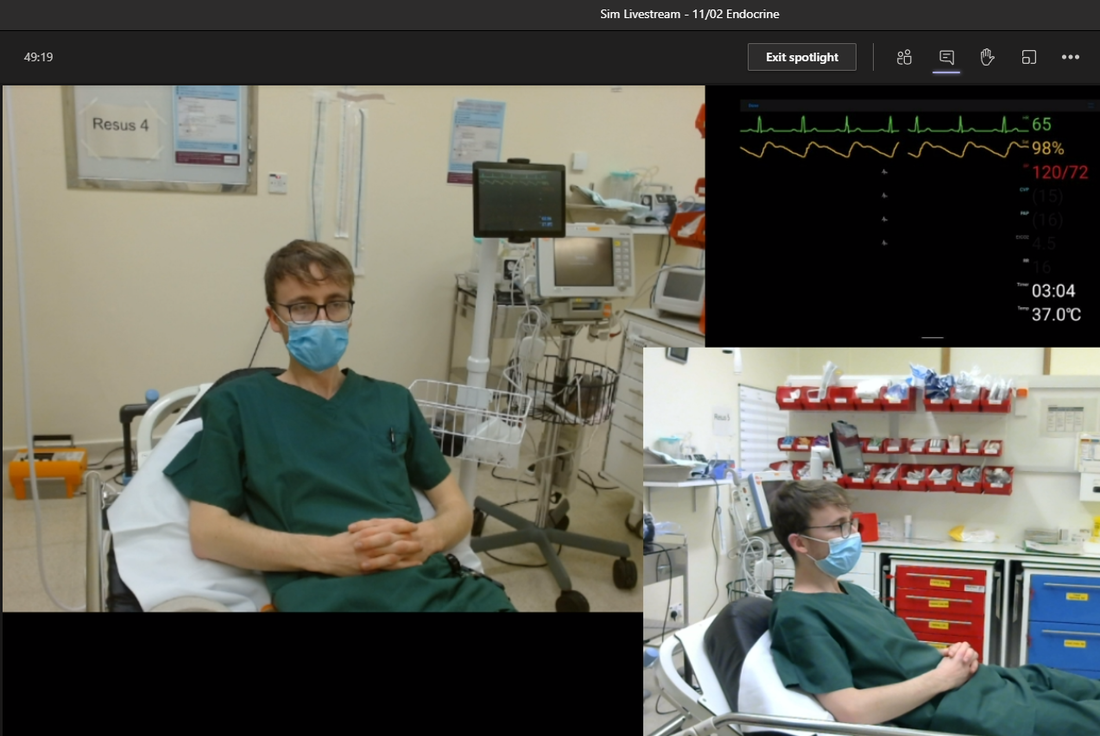

February is endocrine-themed, and I’ve tried to pick out cases from recent weeks that I have had difficulties with or reflected upon when planning the simulations. Each week I’ve tried to improve the quality of live-streaming, with the aim that we can increase the reach of teaching whilst keeping the numbers of people physically present to a safe amount. Please get in touch if you have ideas about how we can best utilise this. The simulated case: A man in his 40s with a long history of type 1 diabetes, presenting with vomiting. This is the 3rd time in 6 months he’s needed to come to ED with vomiting. He has been continuing his long-acting insulin but has been unable to keep food or water down for 48 hours. Has otherwise had good control of diabetes and did not require admissions prior to 6 months ago. He’s been told he can take domperidone before meals, but to limit its use. What happened? The patient came through START, had bloods including a normal VBG, and moved to majors. He had a nursing assessment and was noted to be tachycardic at ~105. The clinician took a brief history, examined him, and together with a senior doctor prescribed IV fluids and ondansetron. The plan was to assess response to this and if not able to eat or drink a substantial amount he would require admission, plus consultation with the diabetes specialist nursing team. What did we think? In debrief we discussed: Causes and consequences of vomiting with diabetes: A primary concern is diabetic ketoacidosis (see our previous blog on paediatric DKA) which can both be a cause or a consequence of vomiting. If we have a patient with DKA but no obvious infection to trigger it, it can potentially be the point where investigation stops… but it shouldn’t be. Keep your differential wide for potential DKA-triggers, and this includes gastroparesis. Diabetic gastroparesis is a result of chronic damage to the nerves that control the movement of food along the bowel. The movement of food slows down and causes nausea and vomiting. In this case the patient’s blood gas/sugar/ketones were normal and we were not concerned about DKA presently. But without any fluid or food input they remain at risk. Consider the wide differential you have for any patient with vomiting and abdominal pain and work through this here as well. Choice of antiemetic: We talked about how we choose antiemetics in the emergency department. Anecdotally ondansetron is widely used as a first line choice. It is licensed in the UK for post-operative vomiting, and chemotherapy-related vomiting, but is clearly used off-label commonly. How do we decide which to use? Different causes of vomiting act through different pathways and involve different neurotransmitters. Have a read of this blog as a start. The vomiting in this patient’s case is likely visceral from feedback from the bowel, so likely to involve serotonin and dopamine. Ondansetron acts through serotonin predominantly, so may be a good option. A sim participant pointed out we often use prochlorperazine in vertigo. Here the nausea is of a vestibular source, and histamine plays a greater role. Prochlorperazine has a wide range of effects, on dopamine, serotonin and histamine. Cyclizine is a histamine inhibitor so may also be sensible here, although the actual mechanism by which cyclizine reduces nausea and vomiting is not known. As an example of comparative cost, the BNF lists IV ondansetron as generally on the £29.97 or £59.95 price tariff, IV cyclizine is on the £18.75 tariff, and IV prochlorperazine on the £5.23 tariff. What about the dopaminergic aspect though? Haloperidol is an antipsychotic that is licenced for nausea and vomiting postoperatively and in palliative care. It has been investigated as a potential agent to treat gastroparesis-related vomiting in the HUGS trial. It was a retrospective non-blinded study of 52 patients who had gastroparesis confirmed by motility testing, with patients compared to their previous visit to ED. They were given 5mg of IM haloperidol, and statistically significant reductions in need for admission and need for analgesia were observed. Whilst the potential side effects of haloperidol should of course be noted, no significant problems were encountered in the study population. Discharge vs admission: It can feel more difficult to admit someone that has normal blood results in this situation. The consultant pointed out that the patient’s knowledge of sick day rules and their management of blood sugar would be important here. Can they eat a significant amount of food and keep water down? If not it is likely they are coming into the hospital. Referring to diabetes specialist nursing team: The sim participants emphasised that we can refer to the diabetes specialist team from within ED. The hospital daily email from 29/10/20 states “please refer patients ASAP if diabetes input is required”, so if it’s obvious it will be needed, we can go to SALUS and refer early. At time of writing today’s daily email stresses “the diabetes doctors and nursing team are giving advice to referrals via typing on the outcome section of the SALUS data form or on the CPL section of See-EHR. Please refer to these areas for the outcome of remote reviews.” Importance of history and info from prior visits: Helpful information for a patient like this can be gathered from information about their previous visits to ED, or previous discharge summaries. Have they previously been discharged directly? What helped? Have they previously been referred to ITU? Do they have close support from the secondary care diabetes team? Additionally, feedback from participants noted it would be helpful to have additional information about the blood gases here: The blood gas was important here as it told us the patient’s pH was normal, their blood sugar was normal, and there were no obvious problems with their electrolytes. If the patient was entering diabetic ketoacidosis we would expect the pH to be below normal, and the blood sugar to be high. To do: Have a read of the simple explanation of gastroparesis on the NHS website here. It also has an area of dietary tips we can refer patients to try [ ] Read about the HUGS trial for haloperidol in gastroparesis here, or a summary by Salim Rezaie here [ ] Blog on the differing mechanisms of nausea and how we target these - here [ ] If you took part in the sim or watched on the livestream, you can use this blog as a starter to reflect on your own experience of it [ ] Blog by: James Keitley - ED sim fellow, reviewed by Dr Chris Humphries - senior clinical fellow --------------- For clinical decisions please refer directly to primary sources. This blog may not be updated. All images copyright- and attribution-free in the public domain or taken by the author. |

Categories

All

The Derrifoam BlogWelcome to the Derrifoam blog - interesting pictures, numbers, pitfalls and learning points from the last few weeks. Qualityish CPD made quick and easy..... Archives

October 2022

|