|

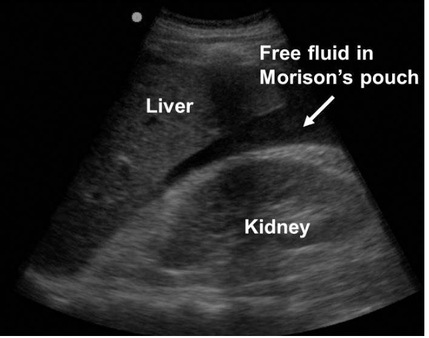

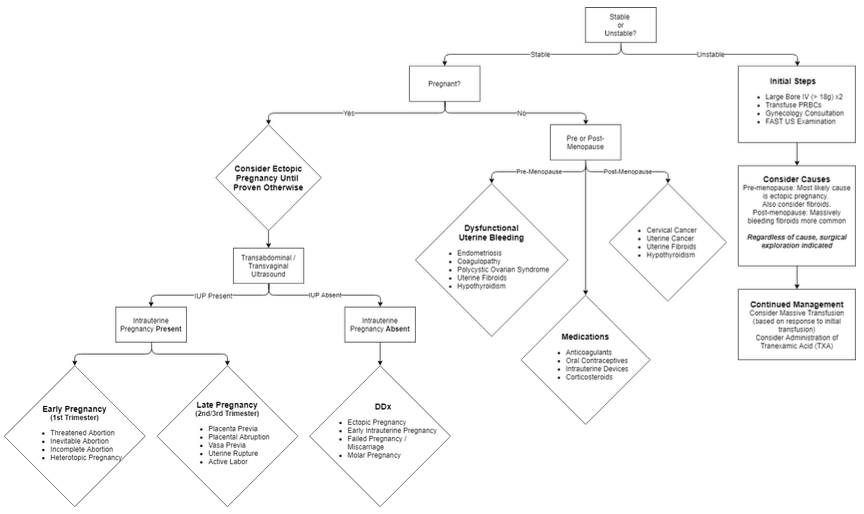

I was recently supposed to have been facilitating a session on vaginal bleeding as part of ACCS teaching so here is my attempt at a little bit of online education. Not my favourite subject on either a personal or professional level and don’t expect me to start speaking like a gynaecologist. A little Covid humour to start: Here goes. Everything an EM doctor needs to know on the glamorous topic of PV bleeding. Keep it simple, stupid: Question 1:Is the woman bleeding so heavily that they are showing signs of haemodynamic compromise? (Are they pale, ashen, sweaty? Peripherally shut down with a tachycardia? Hypotensive?). This is generally not a good sign and might make you feel a bit sweaty too. Take a deep breath, ask for some help and get the patient moved into resus. Take another deep breath and start reciting the alphabet: A and B – pop some oxygen on, C – if you have always wanted to insert a MASSIVE cannula then now is your chance. Two would be even better. Be kind if time allows and use a little local anaesthetic. Take some bloods and send some for an urgent cross-match. If the patient is really unwell then consider activating the massive transfusion protocol and starting a balanced transfusion (PRBC, FFP, platelets). Tranexamic acid is rarely a bad thing when people are bleeding a lot from any cause so think about it early. If you are a bit handy with the ultrasound or can find someone who is then it is worth scanning the abdomen for free fluid (has the patient ruptured an ectopic?). A gynaecologist is going to want to know about this patient sooner rather than later so get on the phone early. The most likely cause of shock due to vaginal bleeding is a ruptured ectopic pregnancy in a pre-menopausal woman and fibroids in a post-menopausal woman. Learning Bite: If the woman presents with signs of shock but with a BRADYCARDIA then you need to think about CERVICAL SHOCK. The patient will feel faint, sick and generally awful with hypotension and bradycardia. In the ED this is usually due to a miscarriage. It occurs when the products of conception pass through the cervix and cause a profound vagal response. The only treatment is to remove the products. This is a relatively simple procedure. The cervix is visualised with a speculum and the products are gently removed with sponge forceps (see below). It is very gratifying thing to do as the woman will literally improve before your eyes. One of our own registrars did this recently with good effect. It is important to think about it as a possibility and as always ask for help. Question 2: Is the woman pregnant? In Emergency medicine the dogma is that we should suspect pregnancy in any woman between the ages of 10 and 50. In reality most women know or recognise the possibility that they might be pregnant so do ask the question first. Establish when their last period was. Ask about symptoms of early pregnancy (e.g. breast tenderness, tiredness, urinary frequency). Try and get a urine sample as quickly as possible. If the pregnancy test is positive then the woman has a RUPTURED ECTOPIC until proven otherwise. Classically a ruptured pregnancy will present 6-8/52 after the woman’s last period. Pain is often more of a feature than bleeding. If the patient is unstable then they will be managed as described above. If the patient is stable then the bottom line is that they need a trans-vaginal ultrasound as soon as possible. This can happen as an in-patient or an outpatient depending on degree of suspicion, extent of symptoms and confidence that the patient will adhere to safety netting precautions if they are allowed home. Please discuss this with a senior and then refer to the gynae team. Make sure they have had the relevant bloods sent first – don’t forget a group and save in case they deteriorate and a serum beta-HCG is helpful as a baseline for the gynae team (they may monitor this serially). Clearly miscarriage is more common than an ectopic but is initially managed in the same way by us in the ED. PV bleeding in late pregnancy obviously has an entirely different differential including placental abruption, placenta previa, uterine rupture and labour. It is very rare to see such patients in our ED as they usually present to labour ward. If they do appear unexpectedly resuscitate as above and seek specialist help EARLY. Question 3: Is the woman pre or post-menopausal? Any woman with post-menopausal bleeding has cancer until proven otherwise. At the time of writing we don’t have access to the 2WW pathways so the patient will need a letter or phone call to their GP to get this sorted. We are now left with a pre-menopausal patient who isn’t haemodynamically compromised and isn’t pregnant. Breath. You now have time to take a bit more of a history! Questions that will help you elucidate what is going on:

So, what can we do in ED? (assuming as always that the patient is not in need of resuscitation)

References and Further Learning

1. NICE guidance on ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng126 2. RCOG guidance on diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy: https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/1471-0528.14189 3. NICE guidance on heavy PV bleeding: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng88/resources/heavy-menstrual-bleeding-assessment-and-management-pdf-1837701412549 4. RCEM learning module on bleeding in pregnancy: https://www.rcemlearning.co.uk/modules/bleeding-in-pregnancy/

2 Comments

Dear all,

As summer appears to have landed, all thoughts of coughs and fevers are surely receding into the background as we queue for our takeaway fish and chips. However, I thought it might be time for an academic update, to remind you that the evidence base around COVID-19 is ever-increasing, and of course there is also a raft of other emergency medicine research worthy of a mention. COVID-19 research “Truth: a fact or belief that is accepted as true.” There is a danger in COVID times that we forget our evidence-based principles and assume that tests that we do for COVID-19 will give us a true answer. More in hope than expectation perhaps. We all know how to assess the performance of a diagnostic test, but of course that depends on how it compares with the gold standard for that disease. This is obviously more difficult to achieve with a new disease, where we don’t have a gold standard, or where the new test forms part of the gold standard. A recent paper in the BMJ also reminds us that the performance of diagnostic tests depends on the population in which the test is applied, and importantly the pre-test probability: https://www.bmj.com/content/369/bmj.m1808 This is well worth a read, and illustrates in clear terms the impact on those who may have false negative tests, and their ongoing probability of having the disease. In addition, for those interested in exploring in more detail how we might define a better gold standard for the diagnosis, those clever people in the centre for evidence-based medicine in Oxford, in collaboration with our own Rick Body from Manchester, have developed a composite reference standard: https://www.cebm.net/covid-19/a-composite-reference-standard-for-covid-19-diagnostic-accuracy-studies-a-roadmap/ Hopefully this will be utilised as a standard in future clinical trials of diagnostic accuracy. Non-COVID evidence In amongst the flurry of COVID-19 activity, you may not have noticed that the LoDED (Level of Detection of troponin in the ED) study results have been published recently in the journal Heart.This may be the signal of a paradigm shift in the way we deal with patients with chest pain in UK emergency departments, and is well worth a read: https://heart.bmj.com/content/early/2020/05/23/heartjnl-2020-316692 This was an emergency medicine-led multi-centre randomised controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness of an early rule out strategy for patients with low risk chest pain, involving early discharge after a single hs-cTn test when the result was below the limit of detection. The good news is that none of the patients who were discharged using this strategy had a major adverse cardiac event within 30 days. In the words of the authors, the LoDED strategy might facilitate safe early discharge in >40% of patients with chest pain. Given that there is a national initiative to get us to walk and cycle everywhere to avoid public transport, should we be cycling to work? Yes, is the answer, but don’t crash your bike: https://www.bmj.com/content/368/bmj.m336 In this UK population-based study, the authors tried to determine whether bicycle commuting is associated with increased risk of injury and whether the health benefits of commuting outweigh the risk with a follow up of 10 years. They compared active and non-active mode of transport in more than 230,000 commuters. 2.5% of the cohort reported cycling as their main form of commuter transport. The study results suggest that commuting by bike is associated with a 45% higher risk of admission to hospital and a 3.4-fold higher risk of a transport-related injury. However, if 1000 participants changed their commute to include cycling for 10 years and associations were causal, it would result in 23 more admissions to hospital (of less than a week) for first injury and three more admissions for a week or more. On the plus side, there would be 15 fewer first cancer diagnoses, four fewer cardiovascular events and three fewer deaths. Stay safe and sane, Jason Smith on behalf of the academic team |

Categories

All

The Derrifoam BlogWelcome to the Derrifoam blog - interesting pictures, numbers, pitfalls and learning points from the last few weeks. Qualityish CPD made quick and easy..... Archives

October 2022

|