Sick kid. Resus. Five Minutes.… There is something about scenarios like this which strike fear into even the experienced amongst us. It’s partly rational: we know that when kids start to decompensate and die from critical illness, they do so really quickly. We recognise that paediatric cases are less familiar and that there are difficulties: the idiosyncrasies of APLS, difficult dose calculations, tiny scaled- down versions of kit. Crucially, kids can’t tell us where it hurts or why they might be sick, so we feel like we’re rooting around in the dark, and then there’s some seriously scared parents to consider. There is also, perhaps, a less rational component. The fear related to dealing with very sick children maybe reflects innate evolutionary hardwiring: the tribe mentality that tells us ‘children shouldn’t die’. Our amygdala goes into overdrive: when confronted with a sick kid, it can be easy to panic and difficult to maintain objectivity. We reflect on how a paediatric resus case reminds us of our own parenting tribulations—sometimes we might even see the face of our own child in those who come into the department. And then there’s the fear of the consequences if it doesn’t go well, as it sometimes does. The stakes—professional, emotional, legal—always seem to be higher where children are concerned. Children up the ante. I doubt many of us will ever find confronting very sick children truly fun, but it should be something we aspire to do well. And if done well, fixing sick kids has to be one of the most rewarding aspects of EM. If critical illness is detected promptly and treated appropriately, children ‘bounce back’ quickly. Parents are hugely grateful. A child with a good outcome might go on to live a healthy life for another fifty, sixty or seventy years. Done well, paediatric resuscitation demonstrates all that is good about being an ED clinician. So how do we achieve greatness in paediatric resuscitation, especially when we don’t see that many really sick kids? One way is to practice together. The department held an in-situ paediatric sim morning on the 22nd November. With participants from EM, Paediatrics, Anaesthetics and ITU, multi-disciplinary teams were put through their paces with three challenging scenarios based on real cases encountered in the ED. These included DKA, Sepsis progressing to PEA cardiac arrest, and near- fatal asthma requiring challenging ventilator strategies. Here’s some key lessons that resulted from the debrief: Lesson One: Treat paediatric resuscitation as you would a trauma call. We wouldn't dream of assessing a sick trauma patient without a team. Why is a very sick child any different? Just as with trauma, approach paediatric resuscitation as a team. Roles should be clearly allocated, a leader clearly identified, and a scribe should be allocated. There will likely be multiple decision makers present from EM, Anaesthesia and Paediatrics. Contributions from all team members should be welcomed, but it should always be easy to identify the team leader. Lesson Two: Need Help? Push the button. Need help now? The paediatric emergency team (PET) is the Hospital Trauma Call equivalent for sick kids. It compromises help from paediatrics, intensive care and also provides additional paediatric nursing support. It’s a great resource. Standard activation criteria for the PET includes cardiac arrest, status epilepticus and reduced consciousness. The criteria are not definitive: as with trauma it is always safer to escalate if in doubt—the team can always stand down later. There’s also the red phone for paediatric anaesthetic support in Plym Theatres. This can be contacted by calling [30949]. Out of hours, the paediatric on call anaesthetist can be contacted through switchboard. Lesson Three: Communication is king. As with so many things in EM, success in paediatric resus really does hinge on effective team communication. We talked a lot about our communication with each other and identified the following strategies as essential during the course of the morning: 1. Give an effective pre-brief. Delivering a formal briefing might feel awkward, but there’s a reason flight crews never get airbourne without one. A good briefing identifies the leader as credible and helps the team prepare, which is an incredibly powerful way of ensuring optimal performance. Here’s a structure I’ve adapted from the Victorian state trauma system:

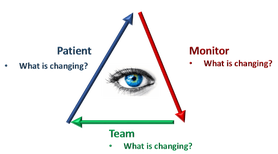

2. Take 10 for 10. At key points during the evolution of the resuscitation scenario, the team leader must ensure there is shared understanding amongst the team, and clearly outline the next steps. One way of doing this is to undertake a ’10 for 10’ summary—that is, spending 10 seconds or so to refocus the team maximise the effectiveness of the next 10 minutes. 3. Task the team effectively. Paediatric resuscitation is not a garden party—there’s no place for the Royal ‘we’! Use names to grab the attention of team members and delegate directly, using closed loop communication for when a task has been completed. Recording names on the whiteboard as part of the briefing can really help. 4. Make a statement! Things change rapidly during resuscitation scenarios, but task focus means not everyone will notice at once. Lack of a shared mental model amongst the team is a common cause of mishaps and can spell disaster for the patient. Making a clear, assertive statement when something big changes gets everyone on the same page. Making explicit use of critical phrases and powerful language such as “this child is now in a PEA cardiac arrest”, makes it clear to the team that it’s time to up the game. 5. Make critical communication routine. The standardised communication strategies outlined above have been developed as a result of research looking at human factors, and are crucial to patient safety. It might be tempting to deviate, especially when working with friends and familiar colleagues. In an emergency with a very sick patient, this should be avoided. Lesson Four: Keep a finger on the pulse. Situational awareness describes the ability of an individual and team to perceive, comprehend information to predict and respond to future events. Put simply, situational awareness is the ability to ‘see around the next corner’. Without situational awareness, crucial things get overlooked, missed or delayed which can have serious consequences for a very sick patient. We discussed a couple of points to optimise situational awareness:

Lesson Five: Avoid assumption.It was Stephen Senegal who asserted that ‘assumption is the mother of all fuck-ups’ in the 1995 film Under Siege. With an IMDB rating of only 5, this quote is probably the only message you need to take away. It’s highly relevant to EM though: think back to the last error you were involved in. I’d be surprised if false assumption did not feature somewhere. There are some ways to defend against assumption: Checklists are a powerful defence against assumption. Key to the third sim case was use of the RSI checklist. Whilst maybe not yet perfectly refined, the checklist serves some vital functions:

Drug Dose Checking. Paediatric drug doses are different to adults. It is possible that neither the clinician prescribing, preparing or administering a drug may have familiarity with it. We have recognised that this situation of the blind leading the blind is potentially dangerous and is presently being addressed with some great work. In the simulation scenarios, clear communication of the sequence of drugs and doses to be given during RSI is essential. Correct labelling of syringes with the drug AND dose provides an essential defence against error. In Summary…. The above is a largely personal reflection of what I gained from participation in a three-hour session. Looking back on it, the amount I learned (and which I will now endeavour to use the next time a sick kid comes into Resus 4) is huge: there is plenty besides which I haven’t touched on. For me, this is proof that multidisciplinary in-situ simulation provides an incredibly effective and high-yield way of learning. Crucially, by allowing teams to work through difficult scenarios in a safe environment simulation teaches us not only learn how to work together but to reframe, as a collective, some of the fear associated with difficult cases involving sick children. Doing a good job is what motivates most of us to do our job, but it’s easier said than done, and I’m aware of the fine and often fragile line that differentiates a good and bad outcome in so much of what we do. Knowledge is one thing, but success is so often dependent on the ‘softer’ stuff: leadership, communication, and team performance. And it is exactly these things that simulation addresses so effectively. I hope that we continue to embrace multidisciplinary simulation within the Department and our Trust: we’ll be all the better for it if we do and, crucially, so will our patients. Dr Blair Graham

0 Comments

|

Categories

All

The Derrifoam BlogWelcome to the Derrifoam blog - interesting pictures, numbers, pitfalls and learning points from the last few weeks. Qualityish CPD made quick and easy..... Archives

October 2022

|